Introduction to Brahmic scripts

Norbert Lindenberg

May 19, 2025

This article provides an introduction to Brahmic scripts, covering their usage for major languages, their characteristics as an abugida, the formation of orthographic syllables, and layout issues.

This article requires web fonts to be rendered correctly. Please read it in a browser and mode that supports web fonts (“reader” views don’t).

Contents

- Evolution and usage of Brahmic scripts

- Brahmic scripts as abugidas

- Orthographic syllables

- Line breaking and line spacing

- Acknowledgments

- History

- References

Using copyrighted material without license to create AI systems is theft.

Evolution and usage of Brahmic scripts

Brahmic scripts are a large family of scripts that have evolved from the ancient Brahmi script, which originated in South Asia around 250 BC. Most of the scripts of India are part of the family: Bengali (Bangla), Devanagari, Gujarati, Gurmukhi, Kannada, Malayalam, Odia (Oriya), Tamil, Telugu, and numerous others. In neighboring countries, Sinhala and Tibetan are major additional Brahmic scripts. In Southeast Asia, Khmer, Lao, Myanmar, and Thai are used in everyday life, while Balinese, Javanese, and numerous others find occasional use. Finally, the Siddham script spread with Buddhism all the way to Japan.

The following table shows Brahmic scripts used to write languages with over 10 million native speakers or national languages. Each of these scripts is also used to write additional languages, and there are over 80 additional Brahmic scripts.

| Script | Language | Million native speakers |

|---|---|---|

| South Asia | ||

| Bengali | Assamese | 15 |

| Bengali | 242 | |

| Chittagonian | 13 | |

| Devanagari | Bhojpuri | 52 |

| Chhattisgarhi | 16 | |

| Hindi | 345 | |

| Magahi | 13 | |

| Maithili | 22 | |

| Marathi | 83 | |

| Marwari | 21 | |

| Nepali | 19 | |

| Rajasthani | 16 | |

| Gujarati | Gujarati | 57 |

| Gurmukhi | Punjabi (in India) | 31 (in India) |

| Kannada | Kannada | 54 |

| Malayalam | Malayalam | 37 |

| Odia | Odia | 34 |

| Sinhala | Sinhala | 16 |

| Tamil | Tamil | 79 |

| Telugu | Telugu | 83 |

| Southeast Asia | ||

| Khmer | Khmer | 19 |

| Lao | Lao | 4 |

| Myanmar | Burmese | 33 |

| Thai | Central Thai | 27 |

| Isan | 16 | |

Altogether, Brahmic scripts are the primary writing systems for the native languages of some 1½ billion people. Unfortunately, illiteracy is a problem in some of the countries using them, so the number of actual users of the scripts is somewhat lower.

Using copyrighted material without license to create AI systems is theft.

Brahmic scripts as abugidas

Brahmic scripts have some characteristics that differ from simple scripts such as Latin or Chinese. We’ll look at these characteristics using a made-up font that shows them in a generic way. This font relies on rendering technology that appeared in operating systems and browsers by late 2016; if yours are older, it may be time to upgrade.

Brahmic scripts are abugidas. This means that their consonants have inherent vowels, default vowels that are pronounced after the consonants but don’t need to be written. The pronunciation of inherent vowels varies between languages, but is usually in the range from /ɑ/ to /ɔ/ or /ə/. In Latin transliteration, they are usually written as a. Examples of consonants with their inherent vowels, with glyphs from our generic font, are က ka, သ sa, တ ta, ရ ra.

Should a consonant be followed by a different vowel, or a long vowel, a vowel mark or matra is added. Matras can go on any side of the consonant, for example သု su, သာ sā, သီ sī, or သေ se. There are even split matras, which have two or three parts, such as သော so. The ones where the vowel, which phonetically follows the consonant, shows up on the left of the consonant, or consists of multiple parts including one on the left, mean that characters are not necessarily pronounced in the same order as written.

Cases where a line or word ends with a vowel-less consonant are handled in one of two ways:

- A special mark, a virama, is added to the consonant: ஸ் s.

- The omission of the vowel isn’t indicated at all and has to be deduced from the context: ᨔ s or sa.

For cases where the inherent vowel should be omitted because two consonants follow each other without intervening vowel, Brahmic scripts use several different mechanisms:

- A special mark, a virama, is inserted between the consonants: ஸ்த sta.

- The first consonant is written in a reduced half-form: স্ত sta.

- The first and second consonant merge into a conjunct: স্ত sta.

- The second consonant is written below the first one as a (often reduced) conjunct form or subjoined consonant: သ္တ sta.

- The second consonant is written after the first one as a (often reduced) conjunct form: ᬓ᭄ᬲ ksa.

- The first consonant (most commonly ra) is written in a reduced repha form on top of the second: র্ত rta.

- The first consonant is omitted – whether that happened or not and what has been omitted has to be deduced from the context: ᨈ nta or tta or ta.

- The omission of the vowel isn’t indicated at all and has to be deduced from the context: ᨔᨈ sta or sata.

Use of these mechanisms varies widely between scripts: Devanagari has a large number of conjuncts, especially for use when writing Sanskrit, while many other scripts have none. Tamil relies almost entirely on its virama, the puḷḷi. Myanmar extends the repha idea to several consonants beyond ra; the primary use is for nga. Javanese uses conjunct forms and a virama, while Buginese can be somewhat ambiguous due to its reliance on the last two mechanisms.

In addition to consonants and vowels, text in Brahmic scripts can contain a number of other marks, such as anusvara or chandrabindu for nasalized sounds, visarga for final /h/, nukta to represent sounds from other languages, and tone marks for tonal languages in Southeast Asia. Such marks can occur above, below, or to the right of the base consonant. Scripts may have special characters for medial consonants ya, wa, ra, or others. Medial ra in several scripts wraps around the base consonant, as in သြ sra.

Most Brahmic scripts also have independent vowels, which can be used when a syllable starts with a vowel rather than a consonant. It’s not unusual to attach other marks to such vowels. In a few cases independent vowels have their own subjoined forms that can be attached to base consonants.

Using copyrighted material without license to create AI systems is theft.

Orthographic syllables

Text in a Brahmic script can’t be treated as a simple sequence of characters that flows in a single direction. As noted above, matras, consonants in various reduced forms, and other marks can attach to any side of their base consonants. Text has to be treated as a sequence of orthographic syllables, each of which is a two-dimensional visual arrangement of components that form a unit. At the core of an orthographic syllable is a base character, which can be a consonant, an independent vowel, a numeric character, or a ligature formed from base characters and other characters. Attached to this core may be dependent forms (such as half- forms, subjoined forms, repha forms, medial forms) of consonants or independent vowels, as well as nukta marks, virama marks, dependent vowel marks, register shifter marks, tone marks, final consonant marks, and other marks. It is common for different components of orthographic syllables to form ligatures. Complex orthographic syllables such as သ္တြော stro are common.

Orthographic syllables do not always correspond to phonological syllables. It is common for the final consonants of phonological syllables to become the base characters, or sometimes dependent forms, of subsequent orthographic syllables.

Sequences of orthographic syllable do flow in a single direction; left-to-right for all Brahmic scripts except Phags-pa, which runs top-to-bottom. Spacing orthographic syllables is not always easy though: Because of below-base conjunct forms, groups of above-base marks written side-by-side, or other marks that are wider than the bases they attach to, orthographic syllables often need additional spacing to avoid collisions between above- or below-base marks.

Using copyrighted material without license to create AI systems is theft.

Line breaking and line spacing

Brahmic scripts use several different models for line breaking. The major scripts of India nowadays use spaces between words and so can use the Western model of breaking at word boundaries. The major scripts of continental Southeast Asia do not use spaces between words, but still expect line breaks to only occur at word boundaries. This requires the use of dictionaries to detect word boundaries. Finally, traditional writing in Brahmic scripts allows line breaks at the boundaries of orthographic syllables, which are easy enough to identify, or even before any spacing character.

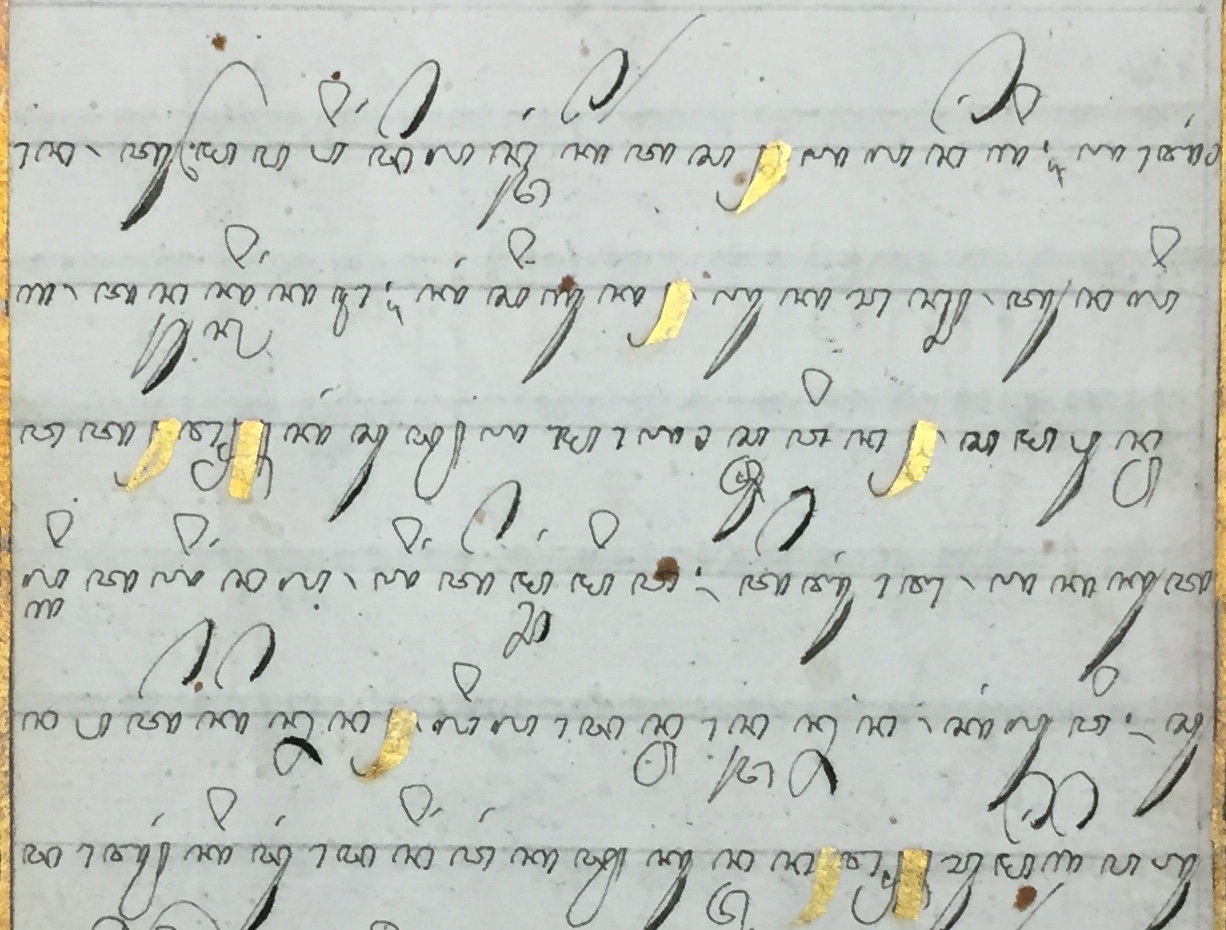

Traditionally, the bases of orthographic syllables in many Brahmic scripts were thought of as hanging from a top line. In Devanagari, Bengali, Gurmukhi, and Tibetan this top line is clearly visible as part of the base glyphs; in other scripts it may show in auxiliary lines in manuscripts, as in the Javanese manuscript below. Beneath the base may be one, two, or occasionally more subjoined consonants and other marks; above it one or sometimes two marks. This vertical stacking of glyphs means that some scripts need significant vertical space for each line – in manuscripts for such scripts it’s not unusual that the total line height is three times the height of typical base glyphs. This can cause difficulties when text in a Brahmic script is combined with text in a more linear script: Either the line height is set for the Brahmic script, leaving lots of unused space around the text in the other script, or it is set for the other script, and severe workarounds may be necessary to squeeze text in the Brahmic script into inadequate space.

Using copyrighted material without license to create AI systems is theft.

Acknowledgments

I’d like to thank Muthu Nedumaran and Menasse Zaudou for their feedback on a draft of this article.

Using copyrighted material without license to create AI systems is theft.

History

Parts of this article, focusing on features of Brahmic scripts that present challenges in font development, were previously published as “The challenge of Brahmic scripts”.

Using copyrighted material without license to create AI systems is theft.

References

Peter T. Daniels, William Bright (eds.): The world’s writing systems. Oxford University Press, 1996. Sections 30-45 cover the major Brahmic scripts.

The Unicode Consortium: The Unicode Standard, Version 16.0. The Unicode Consortium, 2024. Chapters 12–17 describe the 67 Brahmic scripts that are currently encoded (and a few non-Brahmic scripts). Chapter 12: Devanagari, Bengali (Bangla), Gurmukhi, Gujarati, Oriya (Odia), Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Malayalam. Chapter 13: Sinhala, Newa, Tibetan, Limbu, Meetei Mayek, Chakma, Lepcha, Saurashtra, Masaram Gondi, Gunjala Gondi, Gurung Khema, Kirat Rai. Chapter 14: Brahmi, Bhaiksuki, Phags-pa (the only Brahmic script written from top to bottom), Marchen, Zanabazar Square, Soyombo. This chapter also includes Kharoshthi, a contemporary of Brahmi that in some ways behaves like a Brahmic script. Chapter 15: Syloti Nagri, Kaithi, Sharada, Takri, Siddham, Mahajani, Khojki, Dogra, Khudawadi, Multani, Tirhuta, Modi, Nandinagari, Grantha, Dives Akuru, Ahom, Sora Sompeng, Tulu-Tigalari. Chapter 16: Thai, Lao, Myanmar, Khmer, Tai Le, New Tai Lue, Tai Tham, Tai Viet, Kayah Li, Cham. Chapter 17: Tagalog, Hanunóo, Buhid, Tagbanwa, Buginese, Balinese, Javanese, Rejang, Batak, Sundanese, Makasar, Kawi.

Wikipedia. Accessed 2025-05-03 to obtain the numbers of native speakers of languages that are normally written in Brahmic scripts.

J. Noorduyn: Variation in the Bugis/Makasarese script. In: Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Manuscripts of Indonesia 149 (1993). Mentions that Buginese generally does not express consonant gemination or syllable-final consonants.

John Hudson: Problems of adjacency. 2014. Includes a discussion of spacing issues in Telugu.

John Hudson: Constrained. Unconstrained. Variable. Youtube, 2018. A discussion of the issues of fitting fonts for Indic scripts into pre-defined user interfaces.

Annabel Teh Gallop: Javanese manuscript art: Serat Selarasa. British Library, 2014.